Restoring Trust In Science

The Prometheic Oath

By Sharon Kedar, PhD

Trust in science is on the decline – How big a problem is it?

In recent years, especially since the COVID outbreak, there is a general perception that societal trust in science is on the decline. This perception was corroborated by recent surveys [See Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking by Pew Research Center] and while scientists are still viewed as the most trusted group compared to any other professional group, the overall trend is pointing downward.

Among the many scientists who lament this trend there is a general tendency to assign its root cause to misinformation, fake news, and conspiracy theories. This assertion, while true to a certain degree, dodges the core issues. Based on my own experience and perceptions, informed by a science career spanning over thirty years, I would argue that to no small extent scientists are culpable in the erosion of trust in science.

In this article I attempt to address some of the root causes and propose a modest remedy. It is our duty as scientists to be ever self-reflective, and at this critical point in time in which new technology threatens to blur the boundaries between fantasy and reality, and trust in scientists is on the decline, the question: “What can scientists do to restore lost trust?” is particularly pertinent.

Trust in science is a necessity in modern life

The scientific endeavor at its core is a predictive activity. Scientists propose an explanation, a hypothesis, to a natural phenomenon. They test it in a laboratory (physical, natural, or virtual) and based on the test results make predictions about the future behavior of the physical world. A successfully tested hypothesis is presumed true until proven otherwise, at which point it is modified or abandoned for a better one, and the process repeats. That is the scientific method as we know it.

The benefits to humanity from the scientific enterprise thus practiced are exceptional, and for that reason science and scientists have been mostly regarded with highest esteem for centuries.

But here is the rub – verifying the predictions of a hypothesis takes time. Some scientific hypotheses may take years, even decades to be fully tested. Newton’s classical mechanics was considered gospel for over three centuries until, at the turn of the twentieth century, its failure to explain new observations at the smallest and largest scales of the universe gave rise to Quantum Mechanics and Relativity.

What has changed then? Ironically, the very technological breakthroughs enabled by scientific discoveries, transformed society in fundamental ways by speeding up the pace of everyday life. Consequently, the need to rely on the accuracy of scientific predictions in everyday decision-making has become a necessity. Life is no longer moving at the tempo of a cart lazily pulled by horses on a country road. Modern life is akin to driving a finely tuned race-car speeding on a polished racetrack inches away from many other race-cars while being flooded with information about every aspect of your car’s trajectory. In this environment, the immediate consequences of inaccurate information are ever more apparent. Use it to make a false move – and you may crash and burn, and you might take many fellow racers out with you. The timescale of scientific predictions is out of sync with their impact on everyday life - most of them cannot be practically validated before acting on their recommendations.

A prime example of this was the decision regarding whether to vaccinate ourselves and our loved ones during the recent Covid pandemic. Regardless of which side of the dilemma one landed on, it is undeniable that most of humanity had to make a quick decision with potentially far-reaching consequences for the individual and their surroundings, based almost entirely on trust in the scientists who developed and advocated vaccination. It was implicit that if you decided in favor of vaccination that you trusted that due diligence was done to understand and mitigate any near-term adverse reactions and long-term adverse impacts, and that proper analysis of the pros and cons and of alternative approaches both for individuals and for society at large was carried out.

As this example illustrates, nowadays we must act on many similar science-based predictions before we have the time to grasp their consequences, let alone to fully test the hypotheses that underlay them. That, by definition, is trust. In the 21st century the average person has no choice but to trust scientists. Ignore scientific advice at your own peril, and risk being labeled a crank or a conspiracy theorist to boot.

What does trust mean?

A gallant and thorough advance towards understanding the decline in trust in scientists was recently carried out by group of social psychologists from the university of Amsterdam [See How much trust do people have in different types of scientists? by University of Amsterdam] who posed the question: “How social evaluations shape trust in 45 types of scientists”? This careful survey ranked 45 scientific disciplines on their level of trust by several thousand US participants. What is particularly interesting about The U. of Amsterdam study is that it dug deeper and analyzed both the prerequisites to trust, as well as the participants’ willingness to grant influence to scientists of varying disciplines. It revealed, perhaps not surprisingly, that “Competence” and “Morality” are the two dominant prerequisites to trust. This makes intuitive sense far beyond science. The first questions we ask when recommended a mechanic or a contractor are “Are they good?” and “Are they honest?” When we pick a mechanic, we are likely to wonder whether they can find the problem and fix it, but also whether they share our values of being truthful and honest.

The relative weight of the answer to the above questions may differ, though, and this raises the question: What are the consequences of trusting and granting influence to scientists? The answer to the question, as is often the case, is: “It depends.” For example, I would argue that if you really trusted your paleontologist and consequently granted him a supreme decision power on all the fossil-related issues in your affairs, your life in all likelihood will continue unperturbed even if they made a colossal mess of things. By contrast, granting supreme societal influence to epidemiologists and social scientists may have both severe immediate and long-term societal consequences, as the world experienced during the COVID epidemic and its aftermath.

The lure of influence

Over the years I have observed many of my colleagues being interviewed by various media outlets, and I myself was interviewed on a handful of occasions. Most of these were inconsequential interviews for a color story about an interesting scientific tidbit. Some, however, involved questions of societal consequences or implications. Examples are seismologists answering questions immediately after a large earthquake, Climate Scientists discussing the perils of a warming planet, and Medical Doctors and epidemiologists discussing a viral outbreak. My non-scientific observation has been that the larger the consequence and subsequently the societal influence of these public encounters, the easier it is for the interviewee to succumb to the temptation to make grandiose and impactful statements. In some cases, this resulted in scientists crossing over from stating the facts as they know them into making weakly supported behavior and policy recommendations that are not in their realm of expertise.

What drives this temptation to be impactful? In recent decades the world seems to have become runaway popularity contest, and scientists are not immune to this trend. The lure of becoming an “influencer”, or “disruptor” is greater than ever, often with an enticement of a financial gain as a direct consequence of achieving these social status ratings. Scientists have their equivalent social rankings. Every scientific journal is rated by its Impact Factor, the metric index that tabulates the average number of citations received by articles published in a journal over the previous two years, used as a measure of a journal's importance. Every scientist is rated by an h-index, a number that estimates the impact and productivity of a scholar or scientist's body of work. On LinkedIn, the primary professional networking platform, one is constantly watching the number of times their post is “liked”, and the platform constantly sends you reminders that the more you post and liked the more visibility you gain. This bears stark similarity to popularity measures on TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook.

The similarities do not end there. It requires a certain amount of bravery and eccentricity to challenge a popular viewpoint on social network platforms. Similarly, it is becoming exceedingly difficult to challenge scientific consensus in publication or in a public presentation. For example, during the heat of the pandemic, any suggestion that the problem was complex and that we therefore should practice caution before we condemn society to all the unknown and undesirable consequences of lengthy lockdowns was enough to grant one an “anti science” label. Likewise, suggesting caution in mitigating rising global temperatures and not rushing to enforce net zero carbon emissions before we fully understand the economic and societal impacts of such a sweeping policy, is deemed controversial. Pronouncements such as “The debate is over” or “The science is settled” are there to quash an open debate – the heart and soul of the scientific endeavor.

Furthermore, scientific popularity too can be directly monetized, albeit by a different currency: Government and non-government grants and their prerequisites – publications, prestige and influence, and the grand prize: tenureship, which grants faculty members a permanent appointment, securing their academic position and their financial future. The financial rewards from being impactful do not end there. It is common for academic and research institutions to highlight in their annual reports the headlines that the research carried out by the institution’s scientists made in influential newspapers, such as the New York Times or Times magazine. The cover of Nature magazine, a for-profit scientific journal, is another common badge of scientific achievement. In this environment a positive feedback loop is created between the pressure to be impactful and the scientific, societal, and ultimately financial reward system. Academic institutions are complicit in it, capitalizing on their scientists’ popularity and using it to raise funds for their endowments, an increasing portion of their balance sheet.

Under such circumstances there is an incentive to rush to publication and make a scientific “splash”, which often compromises quality. It is difficult for scientists, especially those in the early stages of their career, not to seek popularity and fame, let alone express an opinion that challenges consensus. If you were an early-career post-doctorate scholar or research associate aiming for a permanent faculty position, what incentive would you have not to play the popularity game and capitalize on it? In fact, an argument could be made, that it is your moral duty to your dependents to do so in order to financially support them and secure their future. Being a stoic purist is the privilege of those whose career is secured. What could an aspiring young scientist possibly gain by “just doing good science” and quietly waiting to be recognized for his or her contribution, skills, and integrity?

“Follow the Science”: The flood of information, and the elevation of the stature of scientists

All of the above came to a head during the COVID pandemic. In his book “The psychology of Totalitarianism”, the Belgian clinical psychologist Mattias Desmet describes how in recent years scientists have been elevated to the status of modern “shamans”. An overwhelming flood of information in an increasingly complex, fast-paced world resulted in endowing our expert class with unprecedented powers. This became more apparent than ever during the pandemic, when an urgent global crisis required an immediate and drastic action on an unprecedented scale. During the pandemic, very few of us had the tools to access and understand the scientific papers, which were published in the most prestigious medical journals, and which provided impetus for a global societal shutdown (See Washington Post Article, March 17, 2020). Furthermore, even among those who did have access, only a handful of experts had the time and knowledge to reanalyze the published data and draw independent conclusions. At a time of such an apparent urgent global crisis trust in the experts was paramount. People trusted that the experts were competent and honest, that the system of independent scientific peer review worked flawlessly even if sped up during a crisis, and that policy makers reached rational conclusions that directly followed from sound scientific reasoning. (It is interesting to note that among those who did study the analysis of the virus data were far from unanimous in their conclusions. As we learned much later, many of the voices that advocated caution rather than radical steps were suppressed for reasons that Desmet analyzes in his book but that are beyond the scope of this article.) In reality, most politicians, policy makers, and government officers – the people entrusted with making, implementing, and managing reasoned policy – did not have the expert knowledge to conduct an independent assessment of scientific data, and so they too “followed the science”. “Follow the science” became the battle cry of those who advocated for and abided by closures of public spaces, masking, and mandatory vaccination. Sadly, for the reasons described above, that same battle cry gave scientists the license to cross the line from trusted brokers of information to de-facto policymakers and advocates.

In a scientific world that was already encouraging scientists to be “impactful”, this was a combustive mixture. Post-pandemic it became apparent that, not surprisingly, the data and the conclusions from it had many more shades of gray than the public was led to believe in the heat of the crisis. We may never know how many people unnecessarily lost their livelihood and dignity because they were deemed “non-essential”, how many of our elders needlessly perished in loneliness, and how many of our youngsters suffered irreparable psychological and intellectual damage from being separated from their peers and from their schools for over two years. The precise numbers are difficult to estimate. They may be exaggerated by some and downplayed by others. Regardless, the perception that scientists overplayed their knowledge and that they were not 100% truthful has taken hold, and the damage to trust in science has been done.

"You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

[Richard Feynman]

Following the science is hard

One of my favorite quotes from the famed physicist Richard Feynman is “I know how hard it is to really know something” or in a different variant: "You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool”. This was brilliantly captured in Gary Larson’s Farside cartoon in which a small-stature physicist hotly argues for his favored “Little Bang” theory.

Scientists are human, driven by the same human needs, desires, and fears as the rest of humanity. Recognizing this, the scientific method has evolved to place safeguards in order to prevent us scientists from fooling ourselves. At the foundation of these safeguards is the scrutiny of our work by colleagues who are not emotionally or otherwise invested in the outcome, and whose sole interest is the pursuit of truth. This is carried out through peer review, public presentations and the active seeking out of critical review. Thus, scientists too must trust their colleagues. Tools such as peer reviews and public presentations and debate help in that regard, but it ultimately boils down to trust as well. Like the rest of society, scientists trust each other to be competent and moral, because in a complex, fast-paced world flooded with information, and driven in no small part by the need to be impactful, it is much easier to fool and be fooled.

Navigating to safer waters – The pursuit of truth

The desire to be impactful is not necessarily bad in and of itself. It is a distinct human trait, which can be and has been a very strong driver for good. Why would one venture into scientific exploration if not for the desire to make a positive impact for the benefit of humanity? This can be in the form of curing cancer and saving lives, preventing the spread of a pandemic, preserving a pristine environment for future generations, or more generally in the form of improving our understanding of the world in which we thrive. As I argue above, at the root of the damage to trust in science is that in recent years the emphasis was placed on the wrong kind of impact. A good scientist is analogous to a good artisan - she knows her craft and holds herself to the highest standard (i.e. works hard at not fooling herself). She makes her impact incrementally and carefully, and is not driven by the need to become a “disruptor” or an “influencer”. If she is fortunate and insightful, it is possible that some of her incremental advances of knowledge may become “disruptive”, but that is not an inherent goal of practicing her craft. Albert Einstein did not set out to change the world. He was fascinated with the meaning of time, and his thought experiments ultimately did change the world, but that was because he had the sense and foresight to ask a uniquely interesting question and the extraordinary mental capacity to answer it.

What, then, is the defining characteristic of the right kind pursuit of impact? To answer this question, scientists must be aware of the underlying motives of their scientific quest as they embark on the challenging quest of unraveling new information about our universe. In a scene from in the movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade the hero is faced with the question: “Ask yourself why do you seek the cup of Christ, is it for his glory or yours?” By analogy, scientists must be aware of the motives of their inquiry: “Ask yourself why do you seek an answer, is it for the pursuit of truth or of acclaim?” Seeking and gifting knowledge on behalf of humanity is a privilege that few are fortunate to practice. Using it for personal gain lays the scientific foundations on unethical and unstable soil. If we are invested in the answers to the questions we pose, it is likely to make us pose ill-formed hypotheses, bias our answers, and act aloof from those who sent us on our quest in the first place.

In order to restore the role of scientists as trustworthy and cautious brokers of quantifiable information, scientists must therefore renew their commitment to the core sceintific values that sprang out of the principles of The Enlightenment: The belief in reason and in the idea that the human condition can be improved through rational thought and empirical evidence, but also the belief in individual rights and personal liberty. As the U. of Amsterdam study confirms some several hundred years after the emergence of The Enlightenment, the modern-day children of The Enlightenment intuit that sound reason and the right to reason - competence and morality - are inseparable. Without the belief in the right of lay people to reason for themselves, and the respect for their ability to do so, the scientific endeavor operates in a vacuum. If experts claim the societal mantle of modern-day priests who are the sole conduit to the truth, then despite the tremendous science-driven technological achievements and progress, humanity is doomed to revert to intellectual dark ages and servitude.

To avoid that, subject matter experts must practice humility and constantly remind themselves of the motives for their quest. They must respect lay people by providing them with the unvarnished facts, and trust their ability to decide for themselves, even if they ultimately disagree with those decisions. Conversely, lay people must be confident that great precautions were taken when interpretation is necessary to facilitate the dissemination of information: That the assumptions are well articulated and complete, the dependence of the conclusions on the assumptions is explained, and the uncertainty in the conclusions - quantified. Most importantly, they must be certain that opinions are not masked as facts, and that when opinion is voiced it is explicitly expressed as such.

Taking an Oath of integrity

Upon graduation from medical school, young doctors usually take the Hippocratic oath, a solemn pledge outlining ethical principles and guidelines for their practice. The oath, attributed to Hippocrates, the Greek physician and philosopher, has evolved over the years. A modern version written in 1964 by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, is used in many medical schools today:

“I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures which are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug.

I will not be ashamed to say "I know not," nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient's recovery.

I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know. Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty. Above all, I must not play at God.

I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person's family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick.

I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.

If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.”

In reading the Hippocratic Oath one is struck by both the humility physicians pledge to practice with regards to their own abilities, and by the respect they pledge to have in their patients. Intriguingly, scientists do not have an equivalent oath. The practice of ethical science is implicit, and it is expected that scientists, the experienced as well as the newly graduated, will intuitively know what practicing science ethically means. It is my opinion that now more than ever, when humanity is flooded with information in a fast-paced world, when trust in science is on the decline, and when the temptation to be impactful risks clouding sound scientific judgment and advice, a Hippocratic Oath for scientists is necessary. Some may argue that an oath is insufficient, as doctors, being human, do violate their oath on occasion. I would counter that having an oath places a necessary hurdle against unethical behavior, and having one is definitely preferable to having none.

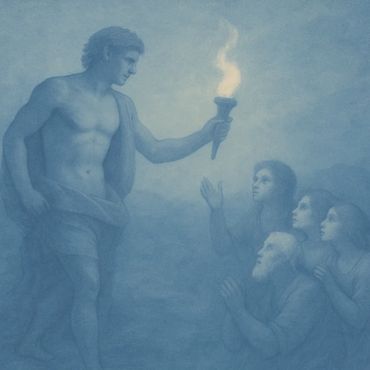

Below is an oath for scientists to pledge and follow, which is based on the Hippocratic Oath. Like the Hippocratic oath, it can be recited at graduation, but it can also be pledged and signed individually (see The Oath). It is named after Prometheus, the Greek mythological Titan, famous for stealing fire from Olympus and giving it to humanity, which brought advancements in technology, knowledge, and civilization. It is appropriate to name such an oath after a figure that represents that knowledge should be owned by all, and not by a chosen few.

-------------------- The prometheic oath --------------------

“I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will remember that there is art to science, and that understanding and respect of others are as important as knowledge itself.

I will not be ashamed to say, "I do not know," nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when another’s skills are needed.

I will respect my fellow human beings’ ability and right to reason and make decisions for themselves. Most importantly, I must tread with care in matters that affect a large portion of society. Giving knowledge to others is an awesome responsibility that must be undertaken humbly and with awareness of my own limitations.

I must take all precautions the scientific method places at my disposal so that I do not fool myself because, if I do, I will surely fool others.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings. When conveying knowledge, I shall clearly articulate my assumptions and how my conclusions depend on them. I shall quantify the uncertainty of my conclusions, and I shall never present my opinions as facts.

If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act to preserve the finest traditions of my calling, and may I long experience the joy of bestowing knowledge with those who seek my help.”

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.